Scam City

How Valerie Harper’s short-lived sitcom became part of a shady market research scheme

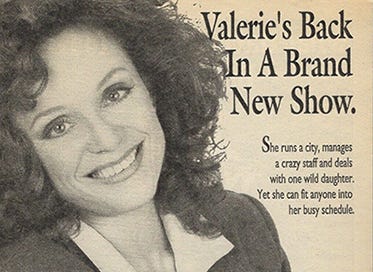

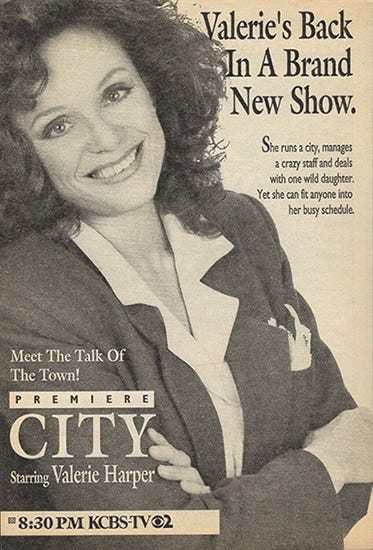

After she won her lawsuit against the producers and network that summarily dismissed her from her own show, Valerie Harper tried to make a fresh start at a new network with a brand new sitcom called City. In the new show, Harper played Liz Gianni, a city manager and single mom of a 19-year-old college dropout. The show followed Liz as she dealt with the bureaucratic duties of her job, the zany antics of her kooky staff, and her daughter’s many problems.

The pilot of City premiered on January 29th, 1990. It had Liz auditioning citizens for a new city theme song, struggling to sort out a construction mess that bulldozed a cemetery and sent coffins sliding across city lines, and dealing with her daughter’s penchant for older men.

While the premise of City was very different from Valerie (renamed The Hogan Family after Harper got the boot), it was clear that this show was Harper’s subtle way of getting back at the network that screwed her. It aired opposite The Hogan Family and featured a few similarities: In both shows, Harper’s character had a husband named Michael and a child played by a Ponce sibling—LuAnne Ponce played Liz’s daughter Penny in City, and her brother, Dan Ponce, played Valerie’s son Willie in Valerie.

Despite its initial good ratings, City waned in popularity as the show went on, and the network chose not to renew it for a second season. After 13 episodes, City disappeared from the airwaves. No one would’ve ever seen or heard about it again if it hadn’t been for a bizarre market research practice that began popping up around the world nearly a decade later.

You Have Been Selected

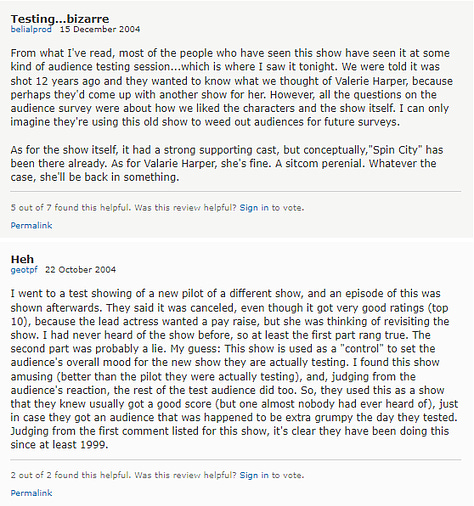

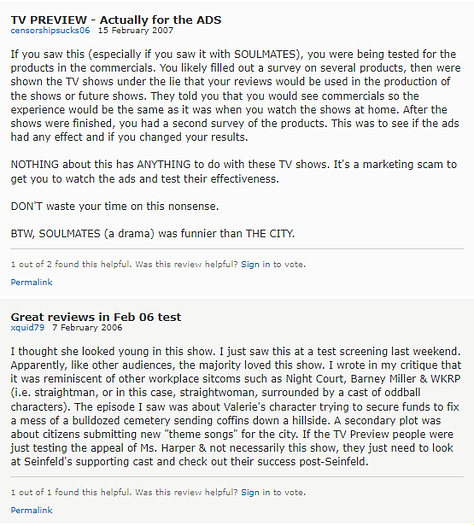

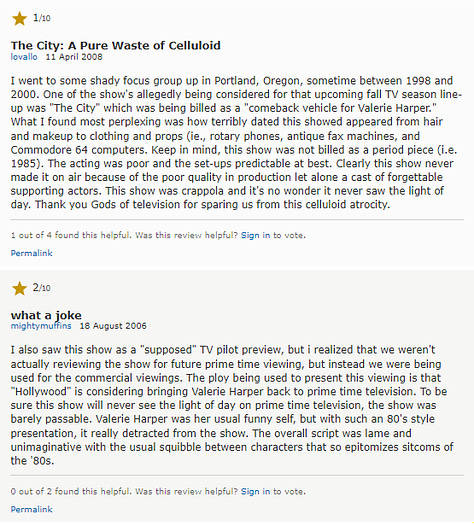

I stumbled across this fascinating phenomenon while doing research for This Week in Sitcom History. The final episode of City, “Just a Passing Dad,” aired June 8th, 1990 (you can watch it here). When I looked up the show on IMDb, I found a curious trend in the user reviews: Most of the reviewers claimed to have seen the show at some sort of screening in the early 2000s.

Intrigued, I checked the show’s Wikipedia page and found a reference to a company called Television Preview, and from there I dove head-first into a deep rabbit hole in the market research world to which only a select few are privy.

From 1999 to 2010, Television Preview showed the City pilot at a series of screenings throughout the US, UK, and Canada. Those who were suckered into attending these screenings were so confused and frustrated that many took to IMDb to vent their rage in the show’s reviews. I compiled the following description of a typical screening event from dozens of reviews, blogs, forums, and message boards throughout the internet.

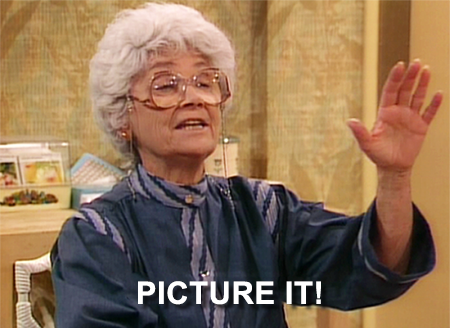

Picture it: It’s sometime in the early 2000s. You receive an invitation in the mail that reads as follows:

DEAR TELEVIEWER:

YOU HAVE BEEN SELECTED TO PARTICIPATE IN A SURVEY WHOSE FINDINGS WILL DIRECTLY INFLUENCE WHAT YOU SEE ON TELEVISION IN THE FUTURE.

YOU HAVE BEEN SELECTED TO EVALUATE NOT-YET-RELEASED TELEVISION MATERIAL THAT IS BEING CONSIDERED FOR NATIONWIDE BROADCAST.

YOU HAVE BEEN SELECTED TO HELP REPRESENT TELEVISION VIEWING PREFERENCES OF THE ENTIRE COUNTRY.

Wow! Lucky you! You’re part of an elite group that gets to decide what everyone watches on TV!

The letter goes on to explain that if you choose to participate, you’ll be entered into a drawing to win a prize package worth $250.

Cha-ching!

Enclosed are four sleek green invitations to an event at a local hotel conference room probably around 6:45 on a Friday night.

You drive out to the hotel at the designated time and proudly present your ticket at the door. Someone hands you a thick sealed envelope (or black folder) and directs you to join the other 175 to 200 people sitting in front of a row of three or four modestly-sized television sets.

The host (who might be a guy in a cheap suit named Mike Forsyth or a guy with a slight British accent) explains that “the people associated with national television have asked us to show you this material” and that your opinion will help decide what will and won’t make it onto TV next season. He then informs you that they have included commercials in the program to simulate a “natural environment,” or make the experience feel like you’re watching TV at home. He advises you to grab a glass of water now because you won’t be able to leave until the screening is over, which could be as late as 10pm.

You’re slightly less excited now, but you grab your glass of water and take your seat anyway.

The host asks you to open your packet and fill out the first questionnaire, which is eight pages of photos of products like air freshener, paper towels, toothpaste, and Brillo pads. The instructions say to “circle the one you truly want.” The host explains that this questionnaire is to determine what they’ll include in your prize package if you win the drawing.

Well, that’s cool, I guess. At least you get to pick your prizes, even though they’re all pretty boring household items.

Now it’s finally time for the TV screening to begin. The host pops a VHS tape into the VCR, and you settle into your plastic chair, ready to consume some fresh new content.

The first show is called either Soul Mates, Blind Men, or Dads. As you watch, you notice two things:

The show looks old. You recognize some of the actors, but they look younger than they look today, and their clothes and hairstyles are old-fashioned. Even the tape itself appears to be worn, and white lines continually flash across the screen.

There are a lot of commercials. I mean a lot. Way more than you would normally see during a half-hour TV program. And the commercials look old too. Some of them aren’t even finished, just showing still shots of storyboards. The commercials are for products like trash bags, snack foods, hair color, and lots and lots of prescription drugs.

The end credits roll and reveal that the episode was shot in 1997 or 1998.

Say what? You thought you were here to give your opinion on a new TV pilot. They made this show years ago and it’s never been picked up? Why are they still bothering to show it? And why were there so many commercials?

The host instructs you to fill out the second questionnaire, which begins by asking what you thought of the actors’ performances and whether you thought the chemistry between them “sizzled.” The remaining 40 or so questions ask you about things like dandruff, heartburn, weight, asthma, anxiety, depression, migraines, and diabetes.

What in the world does all that stuff have to do with a TV show?

The host then asks you to fill out yet another questionnaire to determine what’ll be included in a second prize package.

It’s all the same stuff, but you shrug and circle your preferred products again.

Once everyone has filled out their lengthy questionnaires, it’s time for the next show. The host prefaces this one by explaining that either Valerie Harper, producer Paul Haggis, or just “Hollywood” is looking for a “comeback vehicle” for Valerie Harper, and they want to see what viewers think of her. He either tells you that this is a pilot for a potential new show starring Harper or that it’s an old pilot that was never picked up, and they’re thinking of re-tooling it and bringing it back this fall. Or he might tell you that the show previously aired but was canceled because Harper asked for a raise (which is what actually happened with Valerie).

The TV screens light up with the pilot of City, which looks even older than the last show. The jokes are dated, the actors’ clothes and hairstyles are straight out of the 80s, they use rotary telephones, and Valerie Harper herself looks much younger than she is now. As the credits roll, you notice that the episode was shot in 1990.

Holy Moses, that was between nine and 20 years ago! What’s going on here?

The host then instructs you to fill out another questionnaire with a few questions about the show and many more about your brand and product preferences.

Your writing hand is starting to get sore.

Before you’re allowed to leave, the host says you have to fill out yet another questionnaire that asks about things like your political activity, pets, feelings about GMOs, and what kinds of detergent you buy.

You feel that some of these questions are getting kind of personal, but you’re hungry, tired, and you have to pee, so you hurry up and answer them so you can leave.

When everyone has filled out their questionnaires, the host asks you to hand in your packets. He picks one packet from the pile and tells that person that their prize will come in the mail, but you’re dubious.

Finally, you’re allowed to leave. You rush out the door feeling exhausted and confused and wondering what all that crap was about.

The next day you get a phone call from a company called Datascension. They want to ask you some follow-up questions about the screening. If you don’t answer, they keep calling you every half hour until you do. They might ask one or two questions about the TV episodes you watched, then dozens more about the commercials.

You’re annoyed. Why do they want to know about the commercials? You barely even paid attention to them. You were focusing on the shows because you thought you were supposed to give your opinion about them.

They keep you on the phone for an hour before they finally hang up.

You’re left feeling betrayed and bamboozled. You thought you were reviewing new TV shows that might air this fall. Instead, you watched two old shows and spent hours answering questions about commercials, brands, products, and your personal information.

You wonder if you’ve been scammed somehow. You gave these people your name, address, and phone number. Will you start getting tons of junk mail and telemarketing calls? What’s the catch? What’s their end game?

Copy-Testing: The Method Behind the Madness

Television Preview was a division of a company called RSC The Quality Measurement Company (yes, that’s the whole company name), which was part of a market research firm called ARSgroup. ARSgroup was known for developing something called The ARS Persuasion Score. Comscore, the company that bought ARSgroup in 2010, defines this methodology on their website as follows:

The ARS Persuasion Score, which is a well documented and independently validated measure of advertising effectiveness, measures changes in consumer preference through a simulated purchase exercise with and without exposure to the [commercial]. It quantifies the ability of an ad to influence brand preference, and it has been shown to be predictive of advertising-induced sales at a correlation of 0.90.

The fake TV pilot screenings used a research method called “copy-testing,” where the audience is asked about their brand preferences before and after viewing commercial content to see if their opinions are affected by it.

So why all the subterfuge? According to an employee of Bernett Research (which we’ll discuss later), it was essential that the audience didn’t know they would actually be surveyed about the commercials and not the TV shows. The company wanted to see how well the viewers remembered the commercials if they weren’t specifically told to pay attention to them.

The screening was designed to simulate the home TV viewing environment, where viewers watched TV for the shows, not the commercials. That way, companies could understand which commercials everyday viewers would remember, so they could create content that would stick in viewers’ minds.

Remember: This was at a time when people had to watch TV live and couldn’t skip commercials or pay for premium service to omit them entirely. But I guess ARSgroup didn’t consider those who muted the commercials or got up to pee or get snacks during them.

Do Not Rewind

Between 2001 and 2011, a different form of this research method was reported in the US, UK, Spain, and Chile. Instead of sending out invitations to in-person screenings, a company called Audience Studies, Inc. (or ASI) called people to ask them if they would like to participate in a test viewing of a TV episode.

The following phone script comes straight from an employee of Bernett Research, the company ASI hired to make the calls:

The people who make and sponsor TV programs are interested in your opinions...Today we are inviting a select group of people to watch a new half-hour program...We would like to send you via priority mail a videotape [or DVD] of a half-hour program and ask you to watch it on [an upcoming date]. We will then call you back on [the following day] between 3 and 9pm to get your opinions. Your name will also be entered into two prize drawings for cash and products worth $75 [or $100] each.

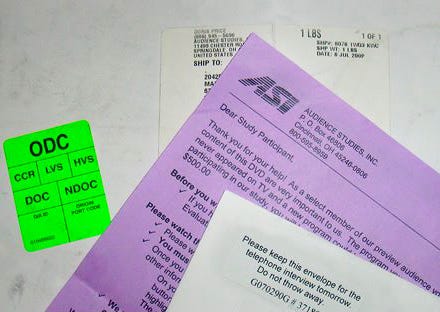

If you agreed, you would receive a package that contained a “self-erasing” videotape labeled “SPECIAL TAPE” with the warning, “DO NOT REWIND.”

Yes, you read that right. The tape was designed to erase itself as it played so you could only watch it once. A strong magnet was attached to the right part of the reel (with either Scotch tape or electrical tape) so that as the tape passed the head of the VCR, it passed the magnet, which erased the tape. Several enterprising individuals who reported receiving one of these tapes said they took them apart and removed the magnets so they could re-use them as blank tapes.

Around 2007, ASI started sending out DVDs instead of tapes, but as far as I know, they weren’t self-erasing, so I guess they relied on the honor system to ensure their viewers only watched them once.

The thick packet of materials included with the tape or DVD provided specific instructions on how to watch it:

You must watch the DVD on a TV (not a computer).

You must watch the program all in one sitting (without breaks).

You must not take notes during the program.

You must not fast forward through the commercials.

The packet also included a “program evaluation” (an 18-page survey), two “entry forms” or “prize selection sheets” (similar to the prize questionnaires from the in-person screenings), and a letter from someone named Doris Price from ASI, which explained that the program on the tape was being considered for a network series, and your feedback would help decide whether or not it would be picked up.

After you watched the program, which was either Dads or The Rocky La Porte Show, you would fill out the program evaluation and presumably mail it back to the company.

The next day, you would get the promised follow-up call from Bernett Research. The caller would start by asking you one question about the episode, then explain that “since we’re interested in your total viewing habits, we would like to ask you a few questions about the commercials during the program.”

They would then proceed to grill you for 45 minutes to an hour about every little detail of each commercial. They would focus on one product—usually Listerine—and ask you 200 questions about whether you use the product and what you think of it. Even if you told the caller that you didn’t watch the commercials or you’ve never used the product, they would continue to ask you every single question. If you refused to answer or didn’t pick up the phone, they would keep calling you every hour between 8am and 8pm every day until they got their answers.

If you were one of the “lucky” ones, you would be asked to watch one more commercial at the end of the tape/DVD, and then you would be grilled about that one.

Finally, the caller would say that you qualify for some free products, but they wouldn’t tell you how or when you might receive them (you won’t). However, one person who watched the DVD version actually reported receiving a $100 American Express gift check.

The caller would then tell you to discard the tape because you wouldn’t be able to watch it again. If you tried to play the tape again, you would find that it was completely blank.

The Connection

Believe it or not, there’s a connection between ASI and Television Preview. ASI is a division of a French market research company called IPSOS. In the early 90s, RSC The Quality Measurement Company (henceforth referred to as “RSC”) began negotiations with IPSOS to form a possible joint venture. The two companies signed confidentiality agreements and exchanged information about their “television advertising research methods,” but they couldn’t reach an agreement and abandoned the project.

In 1996, RSC filed a lawsuit against IPSOS claiming IPSOS incorporated some of RSC’s trade secrets (namely the ARS Persuasion method) into a revised version of IPSOS’s research method, which they called PRE*VISION. In 2000, the court ruled against RSC, stating that IPSOS had “shown that they did not use RSC’s trade secrets in revising PRE*VISION,” but considering the striking similarities between their two methods, I can’t help but wonder if the court may have been wrong. I guess the world will never know.

The Undead Pilots

As for the poor, innocent TV shows that were resurrected for this puzzling scheme, they’ve mostly been lost to time:

Soul Mates (1997) was a fantasy drama starring Kim Raver as a hypnotherapist who had a love affair with a patient whom she believed she knew in a past life. The pilot has been universally panned by those who attended Television Preview screenings. One viewer even said it “should be shown to the prison population as a form of punishment.” Another said it was “funnier than City.” No videos seem to exist of this pilot, and I’m sure that’s no accident.

Dads (1997) was a sitcom about three divorced guys who were all raising young children. People found it dated even for 1997 with its tropes of inept fathers and wise-ass kids who act older than their years. Rue McClanahan appeared in the pilot, and even though she did a half-assed German accent, most people agreed she was the only good thing about it. Whole message boards have been created just for people who saw the Dads pilot—either through a screening or self-erasing tape—to talk about how much it sucked. If you’re some kind of masochist and want to see what all the fuss is about, you can actually watch the pilot here:

Blind Men (1998) was an American remake of a British sitcom about a small business that sold window blinds. It starred Patrick Warburton and Wallace Shawn and received mixed reviews. Some loved it and foolishly hoped it would be picked up; others found it lackluster. Another Blind Men pilot starring French Stewart was attempted in 2001, but that one also failed. Fortunately, it was spared the fate of its predecessor and was never used as a market research gimmick. I wasn’t able to find a video of either pilot or any of the original British series, which was disappointing because I think I would like this show.

The Rocky La Porte Show (2000) was supposed to be a sitcom vehicle for comedian Rocky La Porte, which one blogger described as “an Everybody Loves Raymond clone,” but the pilot never even aired. The few people who saw it seem to hate it even more than Dads. La Porte, on the other hand, seems quite proud of it, as it’s mentioned in all of his publicity materials (although the network cited alternates between NBC and CBS) and he shared it on his YouTube channel. If you’re a glutton for punishment, you can check out the pilot here:

Final Thought

New technology has made these methods of market research pretty much obsolete. I’m sure IPSOS and Comscore have some newfangled internet apps that track people’s commercial viewing habits. If you ask me, that’s a good thing. The people who were suckered into these so-called TV pilot screenings all had negative reactions. They were angry at being duped, frustrated by the endless questions about the commercials, and disappointed that they didn’t get to influence TV programming. While I understand the logic behind the deceit, I can’t get behind any kind of research that toys with people’s emotions like that, especially if it exploits classic sitcoms.

Furthermore, Tony Cacciotti, Valerie Harper’s husband and executive producer of City, was incensed when he found out the show was being used for misleading research studies. He said that he and Harper had no idea Television Preview was showing the pilot to audiences around the world. There were rumors that Cacciotti was planning a lawsuit, but it seems it never happened.

At least one good thing came of this whole mess: City got a second life with a new audience who would never have seen it otherwise. Television Preview’s now defunct website previously reported that 78% of people who watched City said they liked it, even with the poor video quality and constant commercial interruptions. Now that’s a compliment.

Sources

“And Here I Felt Soooo Special,” Maureen Kuppe, I’d Rather Be Blogging, 7/21/2009

“Blind Men,” IMDb

“City,” Academic (Wikipedia)

“City,” IMDb

“Comscore Acquires ARSgroup as Sales Grow,” Chief Marketer, 2/11/2010

“Comscore ARS Research Highlights Importance of Advertising Creative in Building Brand Sales,” Comscore, 10/4/2010

“Dads,” IMDb

“Land of the Lost (Valerie Harper) TV Series: City,” Go Retro, 3/2013

“Marketers Suck,” Kristine Michelle, web-goddess, 2/9/2011

“Revisiting ‘The Rocky LaPorte Show,’ a CBS sitcom pilot from 2000,” Sean L. McCarthy, The Comic’s Comic, 8/1/2014

“RSC Quality Measurement Co. v. IPSOS-ASI, INC., 196 F. Supp. 2d 609 (S.D. Ohio 2002),” Justia, 2/7/2002

“Soul Mates,” IMDb

“Spot the TV ad,” Zach Dubinsky, Now Toronto, 9/7/2000

“Surveys, Rocky LaPorte, Augusten Burroughs, opinion,” everybody’s entitled, 7/25/2007

“Television Preview,” Academic (Wikipedia)

“Television Preview: Thinly-Veiled Ad Focus Groups,” Darren Barefoot, 11/21/2005

Tweet, Emily Higgs Kopin, 9/9/2019

“TV show pilot ‘Dads’ marketing scam,” Matthew Baya, I Paint What I See, 12/9/2003

“Vhs that erases itself,” The Magic Café Forums, 1/2007

“Viewer Discretion Advised,” Nadia Pflaum, The Pitch, 7/15/2004